The Evolution of Distant Learning

And just like that … I’m back! Welcome to the Arrant Artificer, a space intended to explore instructional design through constructive and intellectual conversations between novice and seasoned ID professionals. Over the next several weeks, conversations will focus on the topic of distance learning – what it is, its influences, drivers of its evolution, and its role within the field of instructional design.

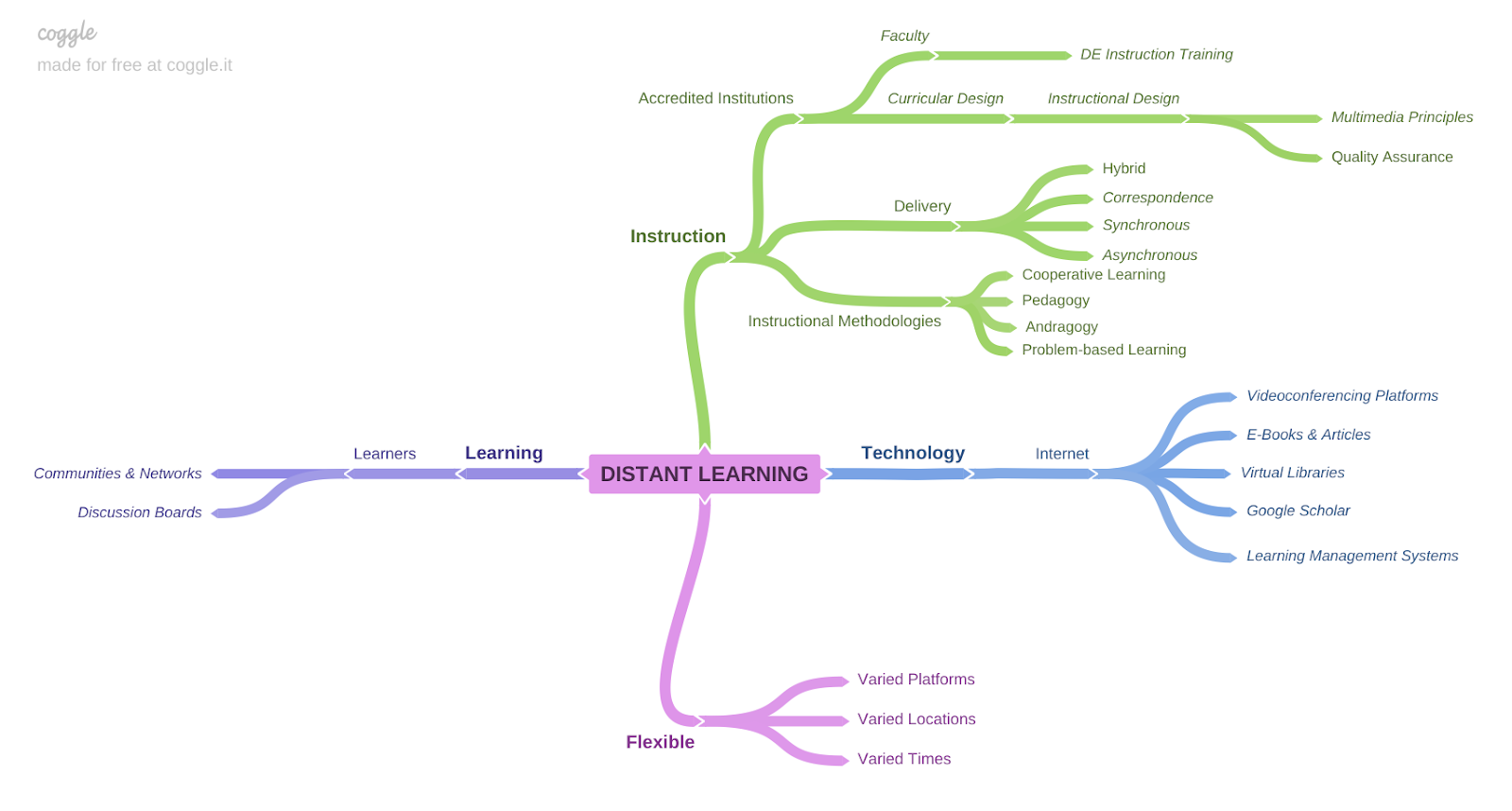

The definition with which I enter

the conversation surrounding the concept of distant learning is that it broadly

encompasses the delivery of instruction for learning to occur in varying geographic

spaces, at varying times, and in diverse ways that allow the learner flexibility

in when, where, and how they learn. A review of resources finds that perceptions

of distance often emerge from perspectives rooted in the professional domain (Simonson

et al., 2019). The resources offer a more universal definition that distinguishes

distant learning as the formal delivery of academic-based, accredited

instruction that is facilitated by an instructor and incorporates interactive

student engagement as required aspects of distant learning (Simonson et al.,

2019). The mind map presented below offers a visual grasp of distant learning.

Distant learning progressed from

its origins of postal correspondence in the 1830s (Simonson et al., 2019) to the

capability for the virtually synchronal instruction that is available and

expected in the 21st Century. The evolution of distant learning is

driven by technological advancements and supported by the emergence of theoretical

frameworks and principles that promote cognitive processing (Mayer, 2014). The

interactive nature of distant learning of today that occurs among learners and faculty

are commonly supported by the vast, worldwide connection of computers that is

the internet. Learners are able to virtually access libraries, classrooms, electronic

books and articles. Use of the internet, video conferencing capabilities, and supporting

software allows for the delivery of instruction to more people located in more

places (Bingham et al., 1996) shifts how instruction is accessed, resources are

retrieved, and learning occurs. These shifts in the academic paradigm logically

influence shifts in how distant learning has been defined over time.

The approximate 400 percent

increase in distant education enrollments in higher within a five-year period

(Laureate Education, LLC, n.d.) is a strong indicator of the popularity of the delivery

medium. The popularity of distant learning extends beyond the domain of higher

education. The conveniences of time, location, and other flexibilities granted

by distant learning have been embraced as a solution for instruction and

learning by various corporate, governmental, and academic sectors at every

level (Moller et al., 2008). Returns on investment have also been realized

through the implementation of distant delivery of instruction. Economic

benefits are achieved through the minimization of personnel needed to facilitate

instructional delivery (Moller et al., 2008). As an example, recent discussions

with a college compliance officer unearthed the realization that smaller

colleges are offsetting budgetary impacts associated with decreased student enrollments

by including distant education instruction to the course loads of faculty thereby

maximizing the use of faculty resources and addressing faculty shortages (M. Gillespie,

personal communication, May 12, 2022). These benefits are fundamental advantages

that education over distance contributes to organizational instruction, training,

and learning. The potential, however, is much greater.

The emergence of companies that

support the global design of courses that are intentionally devised and

delivered to nurture the expansion of knowledge and cognitive growth of

learners offers standardization of digital education. These companies strive

to institute a comprehensive quality assurance system as an essential aspect for

establishing and sustaining the excellence of programs, institutions, and systems

for the delivery of resilient distant education (Kirkpatrick, 2005).

Standardization suggests a broadened potential for the future of the medium

across academic domains and beyond.

As technology continues to advance, distant education will continue to evolve and mature to meet the needs of an evolving society. With the establishment of benchmarks for standardized quality assurance, the design and delivery of methods, materials, and outcomes of digitized instruction and learning become more demonstrable, evaluative, and sustainable. The potential of global standardization can be envisioned as a supporting contributor to the development of a unified, cohesive K-16 educational system that is truly cohesive and equitable in content and delivery. A unified system could minimize the competitive, siloed nature of education and comprehensively realign the focus of instruction and learning for the creation of a more authentic, student-centered, learning experience.

Distant Learning Mind Map

References

Bingham, J., Davis, T., &

Moore, C. (2006). Emerging Technologies in Distance Learning. Horizon

Site. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from

http://horizon.unc.edu/projects/issues/papers/Distance_Learning.html

Kirkpatrick, D. (2005). Quality assurance in open and

distance learning.

Laureate Education

(Producer). (2010). Multimedia learning theory [Video file]. Baltimore,

MD. Author.

Mayer, R. E. (2014). The Cambridge handbook

of multimedia learning. New York:

University of Cambridge.

Moller, L.,

Foshay, W., & Huett, J. (2008). The evolution of distance education:

Implications for instructional design on the potential of the web (Part 1:

Training and development). Tech Trends, 52(3), 70-75.

Simonson, M., Zvacek,

S., & Smaldino, S. (2019). Teaching and learning at a distance:

Foundations of distance education (7th

ed.). Information Age Publishing.

Comments

Post a Comment